It is hard to believe it now but the small and overgrown cemetery at Ballyhogue was once home to a crusading order of knights, whose origins lay in the Holy Land. These were the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem, or as they were more commonly known, the Knights Hospitallers. Founded by the Blessed Gerard following the First Crusade the Hospitallers were a religious order of knights who protected pilgrims to Jerusalem and also fought the Saracens (Muslims). They arrived in Ireland following the Anglo-Norman invasion (1169/1170) and quickly established a preceptory (monastery) at Ballyhogue[i]. From this strategic location overlooking the River Slaney the Hospitallers were expected to defend the new Anglo-Norman colony from attacks by the native Irish.

The order was based at Ballyhogue from at least 1212 AD when the church at Balischauc (Ballyhogue)[ii] was confirmed to the Hospitallers by Pope Celement III[iii]. This preceptory was to be their main base in Wexford until the early 14th century when a second monastery was established at Kilclogan on the Hook peninsula. For the remainder of the medieval period these two Wexford foundations were seen as sister houses, often sharing a preceptor (head monk). Over all control of the Hopitaller Order lay with the Prior of Kilmainham, who was based in Dublin and remarkably two Bree men would hold this prestigious position during the middle ages. They were John Fitzhenry of Macmine castle[iv], who was made Head Prior in 1419, and James Keating of Kilcowanmore[v] (Ballybrennan) who became Head Prior in 1461[vi].

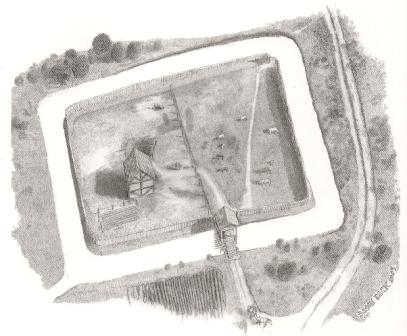

Little if anything now survives of the Hospitaller preceptory at Ballyhogue, apart from the much ruined church of St. John. Originally, however, there would have been a quite an extensive range of buildings. In England, for example, the preceptory generally resembled a secular manor house, with a hall, chapel, kitchen, dormitory and attendant farm buildings[vii] and it’s possible that something similar once existed at Ballyhogue. In 1334 one of these buildings is mentioned when the Prior of Kilmainham granted Fra David FitzDavid of Ballyhogue a ‘stone chamber, which he had built near the gate of this house’. This ‘stone chamber’ may have been large house, hall or even tower, while the presence of a gate suggests that the preceptory at Ballyhogue was enclosed by a wall or bank. Possible evidence for just an enclosing element can be seen on aerial photos which suggest the presence of a large sub-rectangular enclosure immediately to the south of the medieval church of St. John.

The Knights Hospitallers owned extensive lands in the parish of Bree with their original estate corresponding to the medieval of parish of Ballyhogue, which included the modern townlands of Ballyhogue, Galbally, Kereight, Coolfallaun and Ballymorris. They also owned the medieval church at Kilcowanmore (Ballybrennan) and the lands surrounding it, which had been granted to them by the Keating family. To earn extra income the Hopitallers quickly set about renting out these extensive lands to lay tenants. For example in 1311 David de Canton and his wife Agatha held 2 carracutes (roughly 120 acres)[viii] of arable land at Abolsy (location uncertain), for which they paid the Master of Balycaock (Ballyhogue) 40s[ix]. They also owned a fishery, probably on the River Slaney, that was worth 3s. At Quylleferestoun they possessed another 2 carractures of land, which they paid the Master of Balycaock 2 marks[x].

The name of this last location appears to be an amalgamation of the Irish word for forest, coill (quylle), as well as the English words forest (ferest) and town (toun). This suggests that the De Canton’s lands were located within the extensive wood that the Hospitallers owned at Ballyhogue. This forest was quite large, measuring 60 medieval acres in extent in 1338 when Philip FitzPhillip was appointed its custodian (1 medieval acre = 2.5 modern acres). The forest, which must have been an important source of wood for the Hospitallers, survived until at least the the 17th century as it is mentioned in documents dating from 1618[xi] and 1653[xii]

Other lands rented out to lay tenants included 20 acres known as La Pasture, which was granted to Richard de Clerk for 10s per annum in 1321[xiii], while in 1327 David le Corneis was granted a messuage (property plot) at Baliscaoke for 6d[xiv]. Similarly in 1334 Henry Christopher was awarded a Baliscaok owned carrucate of land known as Balygudreman (exact location unknown), 15 acres of which were also held by the chaplain Maurice Hertale[xv]. Slightly further afield, in 1338 the Hospitallers lands around Kilcowanmore Church (Ballybrennan) were rented to Thomas de Sautes for 2s, paid twice yearly. Similarly their lands at Rathnegwe (Ratheenahoon) and Ballysleve (location uncertain, but probably on the slopes of Raheenahoon hill) were granted to Walter Furlong in 1338[xvi]. Indeed, this Walter Furlong may have built the moated site that formerly stood at Raheenahoon in an effort to secure his newly acquired lands.

Additional moated sites on the Hospitaller estate are found at Galbally, Garrenstackle and Ballymorris and these may represent outlying grange farms associated with the monastic order. The Down Survey of 1656 also shows a tower-house/castle at Ballyhogue and this was more than likely built by the Hopitallers, while another tower house at Ballybrennan[xvii] may also have been constructed by the order. There are also the remains of promontory fort at Ballyhogue, possibly built by the Knights, which may represent a ringwork castle, similar to the one found at Dunanore, Bree. As these defensive sites demonstrate one of the Hospitaller’s main roles at Ballyhogue was to act as a protective bulwark against Irish raids.

This is also reflected in documentary sources. For example in 1375 the preceptor of Ballystack (Ballyhogue), John FitzGerald, was ordered to ‘preserve the state of the King’s faithful people, and to conquer rebels’, as well as ‘to maintain a prison’ for the ‘Irish who are not continually at peace’[xviii]. Furthermore he and a number of other ‘keepers of the peace’ were to gather a force of soldiers including ‘men-at-arms, hobelars, horse and foot’ to fight in the ‘marches’ (border lands) of the Wexford colony[xix]. This military expedition, however, proved fruitless and just two years later, in 1377, Fra John FitzGerald and his fellow colonists had to resort to bribery to maintain the peace. FitzGerald was forced to contribute 1 horse and a corslet (a piece of armour) worth a total of 25 marks towards a black rent which was paid to ‘Murgh O’Breen, to prevent the destruction of Leinster’[xx]. This payment amounted to protection money and it clearly illustrates the weakened nature of the Wexford colony by the end of the 14th century.

By the start of the 16th century things had gotten even worse and the Hospitaller’s position at Ballyhogue had become increasingly untenable. The Gaelic Irish were resurgent and the English colony in Wexford was contracting in the face of their advances. The parish of Bree was subsumed into the ‘Fassagh Bantry’ (literally the waste or wilderness of Bantry), an area where English law had little authority. The perilous nature of the Hospitaller position at Ballyhogue is clearly illustrated by a document dating from 1541. This describes how their lands at Whitechurch, Glynn, which were located just a short distance to the south of Bree were ‘waste’ due to the ‘war and rebellions of the Cavenaghes ’[xxi].

It seems that in the face of these Irish attacks the Hospitallers decided to abandon Ballyhogue for the relative safety of their preceptory at Kilclogan in the south of the county. Thus by the Dissolution Edicts of the early 1540’s[xxii], which detail the Hospitaller possessions in Co. Wexford, Ballyhogue is a notable absentee. The Knights had finally conceded defeat and their association with Bree parish had come to an end.

Footnotes

[i] There has been some confusion as to the exact location of this Knights Hospitaller preceptory, with some earlier historians mistakenly identifying it as Ballyhack on the Hook peninsula. Simply a grange of the Cistercian order of Dubrody, Ballyhack had in fact had no connection with Knights Hospitallers, or indeed the Knights Templars. Instead, a carefully examination of the documentary evidence by historian Billy Colfer demonstrated that Ballyhogue, Bree was actually the real location of the Knights of St. John’s preceptory. The final piece of evidence being a grant to Adam Loftus of the Hospitaller lands at Ballykeok, which dated from 1618. This grant included the townlands of Forrest, Kereight, Galbally, Ballymorris and Garrenstackle, all of which, formed part of the medieval parish of Ballyhogue.

[ii] Ballyhogue was known by various names in early documents including, amongst others, Balischauc (1211), Balycaock (1311), Balliscaok (1326), Baliscaoke (1327) Ballystack (1375), Ballykoeke (1581) and Ballykeok (1618), Ballyheoge (1726), Ballykeoge (1760), Ballyhogue (1831)

[iii] McNeill, C. 1932. Registrum de Kilmainham: Register of the Chapter Acts of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem in Ireland, 1326-1339, Irish Manuscripts Commission, Dublin. pp. 138-141

[iv] Hore, P. H. 1911. History of the town and county of Wexford, Vol VI. London. p.282

[v] Colfer, B. 2002. Arrogant Trespass, Anglo-Norman Wexford 1169-1400. Enniscorthy. p.205

[vi] Byrne, N. 2007. The Irish Crusade. A History of the Knights Hospitaller, Knights Templar, and the Knights of Malta, in the South-East of Ireland. Liden Publishing, Dublin. p. 331

[vii] ibid

[viii] One carracture of land was roughly equivalent to 120 acres

[ix] Mills, J. (ed). 1905. Calendar of the Justiciary rolls, or, Proceedings in the Court of the Justiciar of Ireland, H.M. Stationary Office, Dublin, p.159

[x] Ibid, p.160

[xi] Irish Manuscripts Commission, 1966. Calendar of the Irish patent rolls of James I, 1618, Dublin. p. 422

[xii] Extracts from Commonwealth Books, Ulster Office. August 4, 1653, Dudley Colclough. http://www.donconroy.com/news/Chapter%2016%20Family%20docs%20appendix%201581-1873%20ii.pdf

[xiii] McNeill, C. 1932. Registrum de Kilmainham: Register of the Chapter Acts of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem in Ireland, 1326-1339, Irish Manuscripts Commission, Dublin p. 1

[xiv]Ibid, pp. 13-14

[xv] Ibid, p.47

[xvi] Ibid, p. 93

[xvii] Sheil’s History of the Parish of Bree mistakenly identifies this tower house as belonging to the Sinnott family. This Sinnott family were actually associated with Ballybrennan, Tagoat rather that Ballybrennan, Bree. It is also possible that the tower house at Ballybrennan was built by the Keating family, rather than the Hospitallers as they also owned property in Kilcowanmore (although by the 15th/16th century they appear to have been based mainly around the townlands of Ballybrittas/Sparrowsland). Similarly, the Fitzhenry family of Macmine may have built the tower house in the late 16th century when they gained possession of the former Hospitaller lands at Kilcowanmore/Ballybrennan.

[xviii] Patent Roll 49 Edward III, 12th July 1375. http://chancery.tcd.ie/roll/49-Edward-III/Patent. Accessed 30/07/12

[xix] Patent Roll 49 Edward III, 12th July 1375. http://chancery.tcd.ie/roll/49-Edward-III/Patent. Accessed 30/07/12

[xx] Hore, P. H. 1911. History of the town and county of Wexford, Vol VI. London. p. 282

[xxi] White, N.B. 1943. Extents of Irish Monastic possessions 1540–1, Dublin. p.103

[xxii] Ibid, pp. 100-103